The Rights of Avatars

Dr. William Sims Bainbridge

Page 2 of 5

This reminds me of the obscure but very interesting novel, Confessors of the Name by Gladys Schmitt.[1] Set in the early years of the Christian era, it follows a Roman aristocrat as he becomes disillusioned with the values of his society, comes to admire the Christians, and eventually stands with them in the arena to face martyrdom. He never quite winds up being a Christian, because he just doesn't share their faith. Yet as a matter of honor he stands with them, even in the face of death. Was he a Christian martyr? We all play roles all the time, and the issue of authenticity is always with us, not merely with respect to our avatars.

Figure 5: The Author at the Helsinki Transhumanist Conference

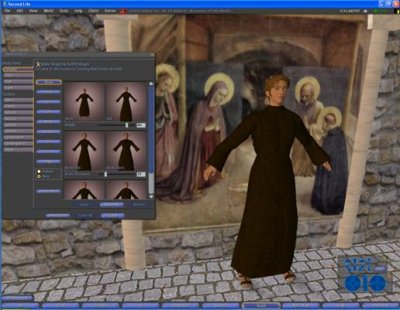

The next time I experienced Second Life, I needed to create an avatar. I wasn't really sure I wanted to, but that was a requirement for entering the virtual world. So I created a male figure that was the exact average on all the variables that could be adjusted. Wanting to alert people that I was a social scientist, I gave him the first name Interviewer, and selected the last name Wilber from a short list offered by SL. Similarly, I really don't want an avatar in There, was forced to create one, and called him Bainbridge. For a while I toyed with making Interviewer Wilber be a priestly character like Maxrohn and Catullus, and Figure 6 shows him being fitted to monastic garb. I did spend a few days walking him around Second Life, but in the end I wished I could get rid of him, and just deal with Second Life myself.

Figure 6: The Author's Superfluous Second Life Avatar

The reason is that I'm not personally very interested in using Second Life as an environment for making friends and sharing social interactions. Rather, I want to engineer things like virtual machines and houses, learn the scripting programming language to create SL software, and examine the things other people have created. Recently, I have begun research on how to create tools to record a person's behavior inside Second Life, part of my long-term plan to develop personality capture software. For experimental purposes, that may inspire me to climb more into the character of Interviewer Wilber so the system can capture aspects of me. But at the present time, his personality is blank. When I set about to create a virtual object or a program in the SL scripting language, his presence on the computer screen is a pure annoyance. This illustrates one extreme across the huge variety of ways that people may relate to synthetic characters in virtual worlds.

The standard notion in Second Life is that the electronic representation of a person is an avatar, expressing the person's real self to a very significant degree, or possibly an ideal self or alternative self that the person is exploring. The term avatar comes from Hindu religion, of course, in which a deity like Vishnu might have ten or more terrestrial manifestations. It is not orthodox to say that Jesus Christ was the avatar of Lord God Jehovah, but the concept is similar: the word made flesh. Classical paganism also possessed the concept that gods were too transcendent to appear within our world as they really are, so when Jupiter wanted to rape Europa, he did so in the guise of a bull. World of Warcraft, in contrast, uses the term character rather than avatar, conceptualizing entities like Lunette as possessions of their user having their own characteristics. Many players call them toons; possibly taking the term from the 1988 movie, Who Framed Roger Rabbit that describes a world in which cartoon characters live alongside humans.

What does this analysis of avatars and toons tell us about the future world in which people may be represented in electronic forms, even long after their biological deaths? Recall the term I introduced at the beginning, cyclone or cybernetic clone. The future of cyclones will not be just a matter of making one, permanent copy of a person. Rather, we will make multiple copies, some identical to each other but existing in different environments or for different purposes, others representing different aspects of the person or alternate identities. Some will be combinations of multiple people, as a child is a genetic mixture of two parents. The rights of cyclones may vary tremendously, as their relations to their owners also vary.

Habeas Corpus

This train of thought immediately suggests we need to think about the relationship between the rights of the owner and of the avatar. How independent is the avatar or character and, thus, its rights from those of the creator? Traditionally, in law, a writ of habeas corpus instructs the authorities to show by what right they hold a person, and here it can be applied to the authority to hold either the user or the character, or both, or the one by the other.

Consider the fact that many of today's virtual worlds need to distinguish children from adults among their users, to protect children from adult predators, or at least to give the appearance of protecting them to avoid legal prosecution and parental anger if something goes wrong. This means that rules are imposed with the age-range of players in mind that have the effect of limiting the freedom of avatars or their operators. For example, the world-like three-dimensional instant messenger chat site for young people, IMVU, says the following in its "safety tips" for users: "Be honest about your age. If you are under 13 and pretend to be older, IMVU will delete your account. If you are over 18 and pretend to be younger to contact underage users, IMVU will delete your account. If you are under 18 and pretend to be older to contact older users, IMVU will delete your account."[2]

The thrice repeated last phrase of this quotation points to a crucial fact about today's virtual worlds: Capital punishment is widespread. Violation of a rule can, and often does, lead to termination of the avatar. As we shall see later, it is seldom possible for an avatar to escape one virtual world and seek refuge in another, so termination equals death. If a child pretends to be an adult, his or her avatar faces the death penalty.

The children's educational world, Whyville, sets very strict limits on free speech by avatars. The user's agreement posted by Numedeon, the company that hosts it, prohibits:

- private or personal information which might identify a user, e.g., full name, telephone number, home address, email address, or instant messaging handles;

- profanity or obscenities;

- personal attacks on other individuals;

- slanderous, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, threatening and harassing comments;

- bigoted, hateful or racially offensive statements;

- vulgar, obscene, discourteous or indecent language or images;

- advertisements or solicitations;

- material or statements that do not generally pertain to the designated topic or theme of any chatroom or message board;

- language that advocates illegal activity or physical harm or discusses illegal activities with the intent to commit them; and

- information that Numedeon deems in its sole discretion to be inappropriate for this Site.[3]

Note the rule against revealing the real-world identity of the person behind the avatar. Similarly, the Habbo Way, the code of ethical conduct for the children's world Habbo Hotel, begins with a prohibition against telling "anyone personal information which could be used to locate you or other people in real life."[4] While perfectly sensible as a way of preventing adults from seducing children, this has the effect of deterring children from making real-world friendships with each other, and may in some cases burden well-meaning adults. The more elaborate virtual world, There, is for persons age 13 and older, with the stipulation that those under 18 need parental supervision. Given a somewhat young clientele, There prohibits many kinds of adult behavior:

In addition to a customizable profanity filter which screens inappropriate language from text chat communications, There enforces strict "PG-13" content standards and takes extra measures to review all items to make sure they meet our content standards before they appear in There. For example, all new avatar clothing items must go through a submissions process which involves full review by a staff member to ensure that they are appropriate before appearing in the shop. Inappropriate submissions, including clothing that makes the avatar appear to be nude, are rejected and will not appear in There.

Content standards are also applied to in-world interaction. Our Behavior Guidelines prohibit explicit sexual language and interactions in There. Members who violate these guidelines will be subject to moderation actions, including their immediate removal from the service for repeated or severe infractions. When a member has been banned, the account is disabled and steps are taken to prevent future log-ins from that machine.[5]

Footnotes

1 2 3 4 5 next page>