Transhuman Parenthood

Sebastian Sethe

page 3 of 4

Why do we need these theories at all? For one, parenthood is not a yes or no question. From a biological perspective, parenthood is  relatively straight forward, or is it? Modern technology complicates things. Consider surrogate motherhood, IVF, cloning, and genetic engineering, where teams of scientists might actually be the biological authors of a section of the chromosome.

relatively straight forward, or is it? Modern technology complicates things. Consider surrogate motherhood, IVF, cloning, and genetic engineering, where teams of scientists might actually be the biological authors of a section of the chromosome.

We do not need technology to render this simple story of genetic contribution obsolete. Consider the father who impregnated the mother and then abandoned the family versus the husbands who take on the role of a loving provider for the child but did not contribute anything to its genome. Surely the law would be well-advised to recognize the latter over the former on account of any of these theories. The law does indeed do so, but reluctantly because it probably fears the infamous slippery slope.

If we start recognizing the adoptive father, where do we stop? What about the nanny who brings the child up? What about the older sister who acts as its most important role model? What about the teacher, who teaches it to think for the first time? All these factors make an important contribution to the future person. This gets messy really fast, and contrary to what some people might believe, the law does not like messy.

How do we bring these considerations to bear? We can begin by drawing a parallel to the intellectual property field. The first correlation is basically the "don't steal my idea" assumption. The invention stems from the author, and there is a moral imperative to acknowledge that relationship of intellectual parenthood, in effect, in law. There is also a best interest argument in IP, which is probably more salient. Only by giving ownership to intellectual assets will we ensure that someone will lovingly convert that useless IP into a socially desirable product.

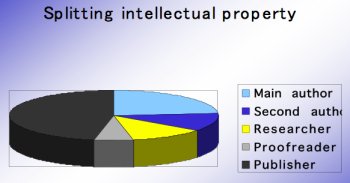

Unless there is some form of legal protection granted over intellectual assets, we will have a tragedy of the commons where authors, inventors and developers will not have any incentive to invest in developing their work. The interesting complication is that there is never a single innovator who can be credited with bringing a completely new idea from the umbrella of the completely unfathomable to the marketplace of applications.

A parallel is emerging, but in IP, we are better equipped to deal with the messiness of life. Image 4 shows an example of a publication to illustrate the concept of co-authorship.

Image 4: Splitting Intellectual Property

Incidentally, this is applicable to other areas of law as well. Tort law is an example of where we account for respective contributions to an injury and apportion responsibility. If we were to regard our human being as an opus or an injury, we have tools to account for respective contributing factors. Yet when we consider it to be a child, we are stuck with very limited options.

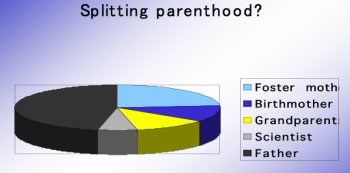

Dare we do this or something like the configuration in image 5?

Image 5: Splitting Parenthood

It is messy, complicated, and not ideal. In IP, we are worried about fragmentation, but things can usually be resolved. Just as a person is named an inventor on a patent, he or she need not be the owner of the patent. The person who receives the patent may not be the person who makes money from that patent, or the person who sells the product.

1 2 3 4 next page>